Welcome to my descent into a mulberry-induced madness.

As I was wandering through the quaint European town of Woodstock, I noticed a most intriguing plaque affixed to one of the houses.

This seems like a curiously specific act to pass! This house is № 28 High Street - so why would Parliament pass an act declaring it to be 1 Mulberry Tree?

My first stop was the Parliamentary Legislation site. A search for acts of 1603 returned just one result:

An Acte for new Executions to be sued againste any which shall hereafter be delivered out of Execution by Priviledge of Parliament, and for discharge of them out of whose custody such persons shall be delivered Privilege of Parliament Act 1603

There are no mentions of Mulberry trees. A search of Parliament for the word "Mulberry" only returns information about the unrelated Mulberry NHS Trust.

OK... Let's look elsewhere. The Visit Woodstock website has this to say about the property.

The ancient mulberry tree still growing in the garden was planted in compliance with a 1603 Act which required inns of a certain standard to plant mulberry trees as a condition of their licence. Cromwell's House

Aha! So this isn't saying that the address is "1 Mulberry Tree" but rather "There is a mulberry tree here as ordered"!

Wikipedia lists all the Acts passed in 1603. The only one listed which looks like it might be relevant is simply entitled "(Inns) c. 9"

The only other information is that the citation for the Inns Act is "1 Jac. I c.9".

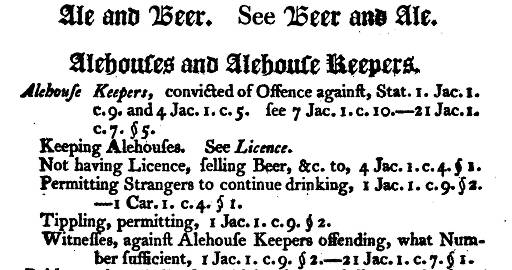

A search for that reference brings us to a book printed 200 years ago - "An index to the statutes at large".

Right! So there's is an Act of around that time which applies to Alehouse Keepers. Presumably, it enforces the planting of a Mulberry tree.

Where is this act?

This is where things get a little more complicated.

But first, a little diversion! I know what you're thinking - why Mulberry trees? It all comes down to King James and his attempt to improve the economy of the UK.

The king wanted to wrest the monopoly of silk-making from the French by cultivating mulberries – the sole food of silkworms. ... Ten thousand trees were imported from all over Europe, and the king required landowners “to purchase and plant mulberry trees at the rate of six shillings per thousand”. The turbulent history of the mulberry by Widget Finn - The Telegraph

There are no sources cited for this claim in The Telegraph, and searching for the quote doesn't produce anything significant. But with a bit of digging, I managed to find this article:

James wrote letters to all his Lord Lieutenants. Appealing to their patriotism, he offered them Mulberry saplings “at the rate of three farthings a plant, or at six shillings the hundred containing five score plants,” or more affordable packets of Mulberry seeds for the less well-off, so that they could establish plantations to feed thousands of silkworms. A Brief History Of London’s Mulberries by Peter Coles

A search for the quoted phrase brings us to John Laurence's "A New System of Agriculture" - written in 1727. It contains the letter written by the King.

Interesting.

The Telegraph article is incorrect - it is only 6 shillings per hundred, not thousand.

This letter was written "in the Sixth Year of England, France and Ireland, and of Scotland the Two and Fortieth." - those dates are relative to his coronations - which places it in the year 1609. That's 6 years after this supposed act, but does provide evidence that James wanted to encourage mulberry cultivation.

Something is amiss, however.

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603 - and her final Parliament was dissolved in 1601. Her successor, King James, assembled his first Parliament in 1604.

Perhaps this act was passed in Elizabeth's final Parliament? According to the History of Parliament, it is unlikely:

Several penal statutes concerning alehouses and drunkenness, blasphemy, regulation of weights and measures, and the enforcement of church attendance were debated at length, though none ultimately passed. The History of Parliament Trust Emphasis added

So this Act was either passed after Elizabeth's Parliament or before James'. Curious...

Back to the search!

I had emailed Parliament to see if they knew anything about Mulberries from 1603. As it turns out, very old Parliamentary texts are not online!

The text of Public Acts dating between 1628-1701 from Statutes of the Realm, and the Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum 1642-1660 are available via British History Online. Apart from these, you will need to consult the paper versions - there are no free online versions available. Parliamentary Archives - emphasis added

I hadn't find anything useful when searching for "1 Jac. I c.9" because the I in there is actually the Roman numeral "Ⅰ". D'oh! What happens if we search for the number 1 in its place?

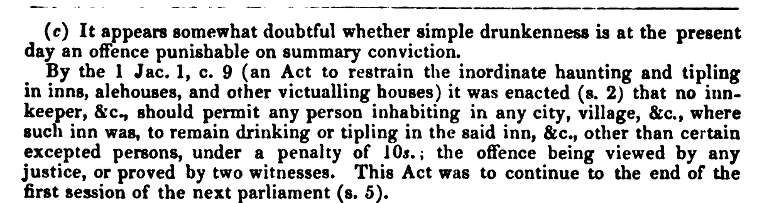

Here's what "1 Jac. 1 c.9" gets us - the 1860 work "Summary of the Duties of a Justice of the Peace Out of Sessions"

We now have a title to search for! "An Act to restrain the inordinate haunting and tipling in inns, alehouses, and other victualling houses".

Note that "tipling" appears to be a mispleling of "tippling" - a British word for drinking alcoholic beverages.

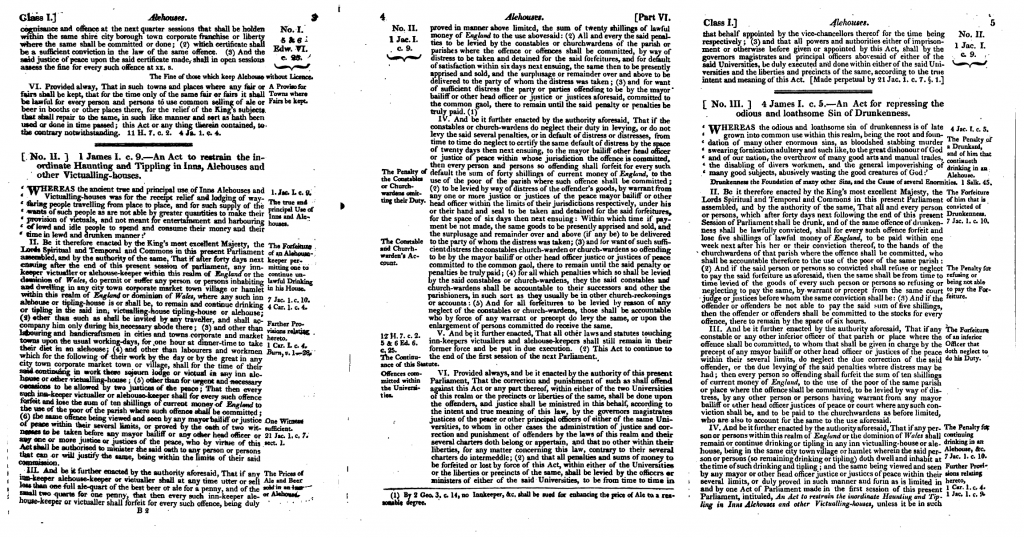

One step closer! With the title in hand, I was able to confirm that the act exists on the Parliamentary Archive site. Of course, they didn't have the full details, but after scouring Google Books I was able find what appears to be the complete text of the act!

Here's "A Collection of Statutes Connected with the General Administration of the Law" from 1836. Click for full-size.

A careful reading reveals absolutely no mention of Mulberries - not trees, nor bushes, nor a solitary berry!

I turned to the National Archives - a search for "Mulberry" in the 1600s returned nothing of value.

What about contemporary reports of when the plaques were erected? They look fairly modern. An article in the Oxford Times refers to them being installed in 2012. It has this to say about the specific plaque:

The Mulberry tree design refers to an Act of Parliament, which said homes could have alcohol sold from them if a Mulberry tree was planted in the garden.

Ah... So perhaps this isn't anything to do with "Inns"! Back to the Wikipedia entry on Acts passed in the 1600s - again, there's nothing obvious in 1603, but I wonder if the date refers to the Parliament of 1604 which ran until 1611. Looking through the titles of various acts, there are several which concern alehouses but none which reference mulberries.

I conducted a more detailed literature search, no books mention Mulberry Trees - even in passing. Surely this would have attracted the attention of a scholar at some point in the last 400 years! I'm not crazy, right? If you found an odd law like that, you'd stick it in a book, wouldn't you?

This was now becoming an unhealthy fixation.

I emailed Dr. David W. Gutzke author of "Alcohol in the British Isles from Roman Times to 1996" to see if he could shed any light on the matter. He couldn't - and suggested that I investigate with local libraries.

To the Oxfordshire History Centre! They were very quick to answer my rambling questions about matters arboreal.

I have checked our catalogues and also various publications relating to Woodstock and victuallers’ licences and I haven’t been able to come up with anything relating to mulberry trees in the context you describe. The Woodstock Borough archive collection deposited with us includes; “Royal Charter of Incorporation” granted by James I 30/Mar 1603 (ref: BOR4/1/D/6). It would require research that would incur charges to investigate whether this was at all relevant, but I have been advised that it would not be expected that something as specific as mulberry trees would be mentioned in this.

Now, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence - but this is now a familiar pattern.

My next stop was the man who carved the plaque - Giles Macdonald. He must know!

From memory it was King James I wanting to kick-start the silk worm industry (to rival continental imports of silk) and apparently they thrive on mulberries!

Perhaps I am going mad?

Who gave Giles the information to carve on these plaques?

There is a leaflet about the plaques on the Woodstock Town Council website which doesn't give any more information about their origin. But that's not the only leaflet available! A different version of the leaflet gives the names of the people who provided historic material for the plaques.

The chair of the Woodstock Literature Society, the curator of the The Oxfordshire Museum, and the Mayor of Woodstock. Had I stumbled into an Agatha Christie novel?

At this point I began to wonder if I was becoming slightly too obsessed. What would these fine and upstanding citizens think of my blundering around casting aspersions on their fine plaques? Thankfully, all were eager to help.

"I was only asked to provide information for some of the plaques, sadly not the one to which you refer and I do not have any further information about it." "I was not really involved in the first round of plaques of which this was one." "Oh, that's to do with King James wanting to improve the silk trade."

At night, I dream ceaselessly of Mulberries.

I tried a different approach. The plaque is affixed to "Cromwell's House" - perhaps a search for that would reveal the truth.

The canonical source for all things Oxford is The Victoria History of the County of Oxford: Volume XII: Wootton Hundred (Southern Part) including Woodstock. A snip at £75 - or freely searchable via British History Online.

There is an incredibly detailed history of the house - but no mention of it being an inn and, you guessed it, no mention of bloody mulberry trees!

It is an ancient and historic house and, as such, is a Grade Ⅱ Listed Building. Sadly, the listing makes no mention of trees in its otherwise substantial history of the building.

My last hope is the tree itself. Surely as noble and historic a tree as this would be subject to a Tree Preservation Order?

I've scoured the web for anything which would indicate that inns were required to plant a Mulberry tree - and I can't find a scrap of evidence for it.

If this was a real law, I would expect the name "Mulberry Tree" to be a fairly popular name for pubs. But this History of Signboards shows by 1864 there were only four pubs of that name in the whole of London - by comparison, there were five Cherry Tree pubs.

There is nothing.

I am nothing.

Perhaps the real Mulberry Tree was the adventure I had along the way?

...And then...

I'd spent the last week emailing anyone who could remotely be connected to this blasted tree. But I hadn't thought to contact the owners of the property. It's a bit rude, isn't it, knocking on someone's door and arguing about their plaque?

One of the historians I had previously contacted was able to forward me an email from the current owners.

They had some notes from when they purchased the property, which were probably written by W Murdock - an Agent of the Blenheim Estate.

Murdock says:

I bought this house in 1937. The vendor had not been able to obtain the original title deeds which were retained by Steele, a butcher in Woodstock (his business premises were bought by Freeman) who, I think, had bought it from the executors of Mr. Ballard, Town Clerk of Woodstock, and a scholar of some distinction.

So far, so good! The ownership ties in with The Victoria History which lists Adolphus Ballard as living there from c. 1890. It was he who spuriously named it Cromwell House.

The document continues:

The following information is, in general, supported by no written evidence, and much of it is surmise The house was built in 1640 as an inn, and was evidently built to attract good custom; it included No 26 and No 30 High Street, and had a range of stables and outhouses facing Rectory Lane. It has an old but flourishing mulberry in the back garden evidently planted in compliance with Act of 1603 (1. James 1) which ordered that all inns and houses of a certain standard should plant a mulberry tree in their grounds.

And this is where local hearsay and reality collide. There is no record that I can find to support the claim that this house was originally developed as an inn. In 1730s, Edmund Sheafe turned part of the plot into an inn - the New Angel. But that's over 100 years after this putative Act.

I suspect that this whole claim is nothing more than an estate agent's exaggeration!

There's a large corpus of absurd English Laws which don't exist - hunting Welshmen with crossbows, taxis needing a bale of hay, that sort of thing. I think that this "law" about inns requiring mulberry trees also goes on the mythical pile.

What have we learned today?

It turns out there's no 1603 law referring to Mulberry trees. There's no law, from any year, that I can find which even remotely mentions mulberries.

- I was shocked that I couldn't resolve this little puzzle within a couple of clicks. I'm used to the world's information being at my fingertips.

- There is a surprising lack of data on the Web about old and obscure topics. I can't understand why the UK Parliament and National Archives don't have easily searchable historic documents like this.

- Google's project to scan out-of-copyright books and make them searchable is of huge benefit to society. Sure, the scans aren't always perfect, and the Google Books interface needs some work - but it is an incredible resource.

- Myths persist. There's obviously a "folk memory" of King James' predilection for Mulberries and this has somehow become commingled with the various laws passed in his reign which targeted inns.

- People are really helpful. Everyone I contacted was happy to lend their time and expertise to help solve this mystery.

- Walking around town and looking at plaques is great fun!

If you have spotted any errors with this post, or have more insight to offer, please stick a comment in the box below.

And, if you've enjoyed this ramble through the past, you can buy me a delicious bottle of Mulberry Gin!

10 thoughts on “By Act of Parliament 1603: One Mulberry Tree”

Richard Gadsden

The reason for the date confusion over 1603/1604 is people failing to understand the dating conventions of pre-nineteenth century acts of parliament.

An Act of Parliament is dated by the regnal year in which began the parliamentary session in which it was enacted.

So 1 Jac 1 (meaning the first year of Jacobus, ie James, the First) means that it was passed in a Parliamentary year that started within the first year of James' reign - which started with the coronation on 25 July 1603. The state opening was 19 March 1604 (see http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1604-1629/survey/parliament-1604-1610 ) - still within the first year - so any law passed in that session is counted as 1 Jac 1. Prorogation was on 7 July 1604, so the Act could have been passed anytime during that period.

But lots of people don't know this, and assume that it means the first year of James I, ie 1603, with 1604 being the second year. This is why you get people "helpfully" transcribing 1 Jac 1 as 1603, when it's actually 1604.

Terence Eden

Ah! Very interesting, thank you 🙂

I will now make it my life mission to place random plaques around the UK just to confuse some future geek.

FYI, I started a project to turn all the volumes of the British Statutes At Large into plain text: http://statutes.org.uk/ Naturally, absences and OCR errors, but it's getting there.

Incidentally, seems like there was mulberry tree legislation in Virginia; for example https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=osROAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121

Jon R

It's worth mentioning as well that before 1752 the legal year began on Lady Day (25 March), so "19th March 1604" for example was actually in 1603.

@YateleyHistory

I have an 'veteran' Mulberry tree in my garden which I erroneously yesterday told a Planning Officer might have been planted in 1603! Quite by chance after she left I found my notes from the Salisbury MSS Vol 18 page 422 headed "Mulberry Trees 1606 - Terms of a patent for Mulberry trees. To be for 2 years. The patentee to bring in only the white mulberry; plants of themselves and not slips of others; and of one year's growth at least; to bring in one million per year; and not to take above a penny for each plant. Undated endorsed 1606, and ny Salisbury "Mulberry Trees". The people who sold me the house told me our mulberry tree had been planted in 1603 and the estates agent's blurb said that the house was built in 1540 - as a hunting lodge in the Windsor Forest (which it wasn't). The Woodland Trust have listed our mulberry as a 'veteran tree' but not as a 'champion tree' as I don't have documentary proof of its planting date. The mulberries are excellent to eat!

I really enjoyed this blog since we have a veteran mulberry in our garden which local legend says was planted in 1603. "By Act of Parliament 1603: One Mulberry Tree" shkspr.mobi/blog/2017/01/d… via @edent

| Reply to original comment on twitter.com

Read it first for the Sunday adventure, read it again with the voice of Alan Bennet. What lovely whimsy!

| Reply to original comment on bsky.app

The Mulberry Tree, by Van Gogh, 1889 It was here we go round the mulberry bush in my garden recently – or rather here we…

| Reply to original comment on thegardenhistory.blog

Trackbacks and Pingbacks

[…] This is a great read. […]