Welcome to NaNoWriMo, where I - and thousands of other plucky souls - try to write a 50,000 word novel in a month.

Welcome to NaNoWriMo, where I - and thousands of other plucky souls - try to write a 50,000 word novel in a month.

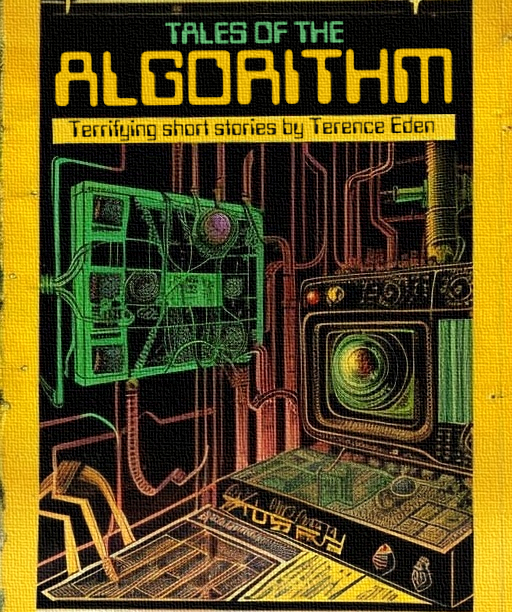

You are reading "Tales of the Algorithm". A compendium of near-future sci-fi stories. Each chapter is a stand-alone adventure set a few days from now.

Everything you read is possible - there's no magic, just sufficiently advanced technology. Think of them as technological campfire horror stories.

Your feedback on each story is very much appreciated.

And so, let's crack on with...

Well you should fear Polythene PAM

I am the loneliest astronaut. A relay somewhere in the space-station clicks and the LED panels above my bunk slowly start to brighten. It isn't as though I've been sleeping, but lying here staring at the ceiling at least lets me pretend this is all just a bad dream. The station is never quiet, there's always a fan humming or a recycler gurgling or a hard disk chuntering. But with no-one else on board, it feels as quiet as a tomb.

Last month Valentina had gone out on a space walk, ostensibly to fix a micrometeoroid-damaged solar panel. She spent a few hours chatting with us as she undertook the repairs. She'd finished taping up the holes and rewiring the delicate structure of the 20 metre flexi-array with about 30 minutes of oxygen left. As we re-energised the panel she began to say her goodbyes. I begged her to come back inside, but she turned her radio off and set her toolbag to autoreturn. From the couplola I watched her drift further and further away until she became just another piece of space junk in a declining orbit. Even if I could have spoken to her, what would I have said? She knew her family were all dead. She knew that staying on the station was tantamount to suicide. So why not take matters into her own hands? At least her sacrifice gave us both a little more time. One less mouth to feed and one less pair of lungs sucking up oxygen. She really did think that she was buying us enough time.

A hundred years of space-flight and the zero-G toilet was still the bane of every astronaut's life. After my morning ablutions, I pulled out the telescope and consulted a tattered print-out which calculated Valentina's likely position. I desperately wanted to see her again even for just a second. I sent radar pulses out, but she was nowhere to be found. I hoped her soul was finally free.

Wiping away my tears, I began the same ritual that I had done over a hundred times. AM and FM were nothing but static. Somewhere in the 25kHz range there was a faint timekeeping signal. No doubt some military installation on a deserted island was still broadcasting. UHF was empty aside from a few crackles of something. It wasn't strong enough to get a lock on. Up and up I dialled, but there was nothing. I switched to the Ku band and heard the lock-on beeps of a targeting computer getting stronger with every pulse.

I was still on Earth when the first major incident happened. A Boeing 797 smashed into the ground just outside Heidelberg with all souls lost. Everyone assumed it was a terrorist campaign - and several groups were quick to claim responsibility - until the investigators found the tell-tale grey sludge dripping from one of the engines. PAM had gotten loose. We didn't know it then, but that was the beginning of the end.

For hundreds of years, goods had been wrapped in paper. But paper is prone to tearing when wet, it rots, it catches fire, it isn't transparent. So the world moved to glass. But despite its excellent thermal and optical properties, glass was heavy and fragile. So we embraced plastics. They were lightweight, flexible, sturdy, noncombustible, and utterly inert. They were perfect! Aside from the fact they were a toxic nightmare. We were drowning in a sea of plastics which couldn't easily be recycled and were leaching chemicals into our bodies and biosphere. Worse still, we were addicted to them. Everything was made of non-biodegradable sheets of plastic.

PAM changed all that. It was a genetically engineered bacteriophage, infused with exotic radiation-blasted eukaryotic microbes, and crossbred with tardigrades. The consortium of German scientists proudly announced their new creation: the "Plastik Auslöschen Mikrotier" (wipe out plastic micro-creature). It was a cute and fuzzy little critter. A six-legged waterbear which would happily chomp through anything plastic. The microscope videos showed it waddling up to a scrap of microplastic torn from a discarded carrier bag. The PAM appeared to sniff the morsel and then devoured it. Over in a second! It could eat several times its initial body weight in plastics before needing to defecate.

Defecation in microorganisms is slightly different from the process you may be familiar with. The PAMs would grow bulkier the more they ate, puffing up like balloon animals. When they reached a critical size they shed their skin, leaving behind the grey and goopy mess which was their faeces. Just like in larger animals, these waste products could be put to good use. The mutant tardigrades had effectively converted waste plastic back into a fuel source.

This was a miracle! Take plastic, add PAM, get fuel. This was going to save the world.

There were only two problems. They were the merest wrinkle in the plan. Tiny details really.

The first was that the super-powered waterbears were horny. They were constantly at it - moreso when they'd been fed. A single male tardigrade could impregnate thousands of females every day. And they would, given half a chance. About two weeks after that magical night, the female would have 30 brand new babies ready to hatch. A couple of weeks later and those freshly hatched eggs reached sexual maturity.

The second problem was that the PAMs were insatiable. Not just for each other, but for their food. They only paused eating in order to mate. They didn't sleep. They didn't enjoy a rich and vibrant nightlife sitting under the stars. They ate, mate, and shat. That's all. When they found a source of plastic, they would eat it all. There was literally no way to stop them.

All of which was manageable. The scientists only bred single-sex PAMs. That way they could control the supply and ensure things didn't get out of hand. The PAM facilities were heavily guarded and had obsessive safety protocols. The PAM were kept in tightly controlled conditions and constantly monitored to ensure they didn't escape. Plastic waste was shipped to the facility, fed to them, and their faecal product was collected and burned. Nothing could go wrong.

And then a PAM escaped. One of the technicians was driving home when his car veered off the autobahn and into a safety barrier. He was mercifully uninjured. The world was not. As the firefighters cut him free, they noticed a grey goo seeping out of the bottom of the car. The tardigrades had enjoyed a bottomless brunch of the plastic insulation within the car. The PAM facility was notified of the containment breach and they did what any reasonable company would have done under the circumstances. They covered it up. The whole area was sealed off, there was mass decontamination, and the whole area was sterilised

It turns out that there were two more problems with PAM. Despite being bred as single sex, they were prone to the odd spot of parthenogenesis. This wasn't a gene-splice gone wrong; it was in their very nature. When faced with an excess of food and a dearth of males, the tardigrades simply gave birth to a few males. And those males went wild. They sowed their oats and created a cataclysmic number of new babies.

The final problem was, in retrospect, obvious. It's impossible to kill a tardigrade. They are extremophiles. They can be found in the deepest arctic ice. They're present in the magma vents of volcanoes. They cannot be irradiated, suffocated, or crushed. Drown them in acid and they'll walk away unharmed. Cover them in liquid nitrogen and they'll survive. Subject them to astonishing atmospheric pressure and they'll bounce back. The attempt to sterilise the scene of the car crash was woefully inadequate.

It's impossible to know how a PAM made it aboard that doomed 797. All it took was a single one. It ate, gave birth, mated, and started the cycle again. If there was plastic, it would find it.

By the time our rocket launched to the space station there were reports of people dropping dead in the streets as PAM ate the plastic in their pacemakers. The launch pad was on the island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe. When the PAM crisis became apparent, we went into a strict lockdown. No ships, no deliveries, no visitors. We naïvely assumed that the scientists would figure out something before we returned.

Valentina and I were warmly welcomed by our old friends, Bradley and Gillespie. As their relief crew, we brought with us much needed food, water, and equipment. And, if they so desired, a way to return to Earth. We spoke long into the night about the risks of returning and the risks of staying. Our new supplies meant that the four of us could stay in our little bubble for several months. Safe from all the concerns of the world. Far away from PAM.

Bradley elected to go home. He missed the Earth so much, and his wife even more. He'd put in a decent shift up among the stars and it was time for him to be with his family. His last words to us were "it is better to die in the free air of home, than live in the recycled BO of this poxy tin can!" Our forced laughter carried him home to his loving wife.

A few weeks after that, we were informed of his death. Despite all the biosecurity efforts in place, a couple of PAM had made their way into a nuclear power station. The devastation was immense. A whole city wiped off the map and there, somewhere in the radioactive rubble, the upgraded tardigrades were unharmed. Valentina's hometown was hit next. A build up of PAM sludge had gone unnoticed in the sewer system. A spark from a chewed up piece of insulation was all it took. The PAM excrement was a wonder-fuel and the whole town burned long into the night.

Gillespie and I were in constant radio contact with Earth and Mars. Communications with home were spotty as NASA, ESA, and ROSCOSMOS struggled to keep broadcasting. Stable power and plastic-free electronics were in short supply. Bluntly, so were our provisions. Deep in the heart of Baikonur, the Russians had managed a complete and effective quarantine against the PAM. With our thanks, they loaded up an old Soyuz full of necessities and blasted it into space.

Mars was on the other side of the solar system. As they scrambled to launch a rescue craft for us, Gillespie and I did some deeply uncomfortable maths. We weren't going to make it back to Earth; that much was clear. Pockets of VHF Radio Hams would keep our spirits up by talking to us, until each one fell off the airwaves. We could see the River Thames on fire from up here. The whole world was slowly being consumed.

The Mars rescue vessel would be with us in 6 months. Assuming the Soyuz reached us, there would be enough food and water for the pair of us to last two months. If we went on a starvation diet, we would last 4 months. This wasn't something we could science our way out of. There was going to be no deus ex machina, no sudden spark of genius, no reversing the polarity of the neutron flow. The harsh truth known by all astronauts is that space hates you and wants you dead. We could scrub our air clean, drink our own recycled piss, and chomp down appetite suppressants. But unless we could figure out how to photosynthesise in the next few weeks, we were both going to die.

I flushed Gillespie's corpse out of the airlock. I had begged and pleaded with him not to do this, but he was unsentimental. He was a man, I was a woman. I needed 10% fewer calories than he did. I had more body fat and therefore needed 5% less water than he did. With a precise and detailed ration plan - which he left me - I would be able to survive until the Martians arrived. Just. It would be tight, but the cold logical maths didn't lie.

The night before he died, Gillespie spent the night in prayer. His suicide note was very tender and said he did not need my forgiveness; he did not consider his self-sacrifice to be a sin. He wrote down several Ayahs, Parashiyots, and Biblical verses which, in his opinion, proved that God was merciful to those who had to choose extreme measures in order to preserve their own life. As such, he relinquished his mortal body to me in the hope that I would find a use for it.

Even with his blessing, I couldn't do it.

The beeping is growing louder now. The automated Soyuz docking computer is entering its final approach. A series of nozzles dotted around its body are puffing out propellant as the craft gently approaches the station. It matches our rotation and velocity. My heartbeat matches the staccato tempo of the beeps until, with a bone shaking thud, the craft are mated. We hang together tail-to-tail like cosmic dragonflies.

I drift over to the hatch. Just beyond are enough Russian supplies to keep me alive. Enough to make Bradley, Valentina, and Gillespie's sacrifices worth it. I watch the pressure gauges equalise and throw open the doors. I float inside the little craft, eager for the taste of fresh fruit.

Every internal surface is dripping with PAM.

Thanks for reading

I'd love your feedback on each chapter. Do you like the style of writing? Was the plot interesting? Did you guess the twist? Please stick a note in the comments to motivate me.

One thought on “Chapter 21 - Well you should fear Polythene PAM”

@Edent@mastodon.social I guessed the twist partway through but it didn't diminish my anguished gasp at the end. Felt like a classic Asimov plot ☺️

| Reply to original comment on ibe.social

More comments on Mastodon.