Chapter 13 - Paperclip Waiter

Welcome to NaNoWriMo, where I - and thousands of other plucky souls - try to write a 50,000 word novel in a month.

Welcome to NaNoWriMo, where I - and thousands of other plucky souls - try to write a 50,000 word novel in a month.

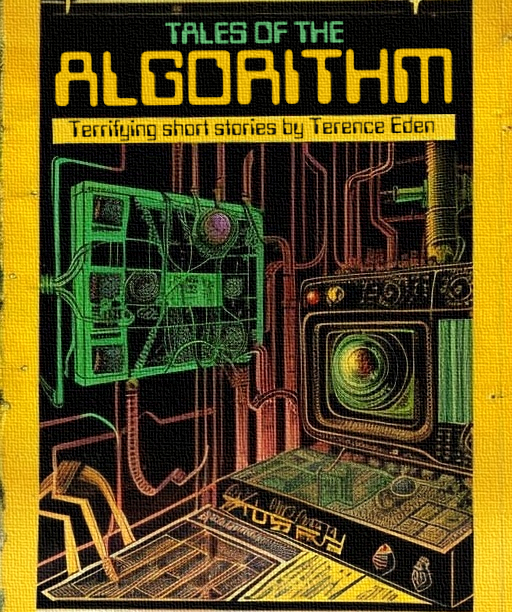

You are reading "Tales of the Algorithm". A compendium of near-future sci-fi stories. Each chapter is a stand-alone adventure set a few days from now.

Everything you read is possible - there's no magic, just sufficiently advanced technology. Think of them as technological campfire horror stories.

Your feedback on each story is very much appreciated.

And so, let's crack on with...

Paperclip Waiter

My great-grandfather - so family legend goes - came to this country with a dream of opening an Indian restaurant and ended up inventing Chicken Tikka Masala. Of course, family legend also says he once served the Queen of England a jalfrezi and later lost a bet with John Lennon over whether he could handle the spice in the house-special vindaloo. Apparently Lennon lost the bet but never paid up. Well, that's how my grandfather tells the story. When daddy tells it, the Queen declared it to be the best jalfrezi in the country and all of The Beatles lost the bet. I wonder if I'll tell my children an equally exaggerated tale? I wonder if anyone will believe me.

One thing that isn't exaggerated is that my great-grandfather had a talent for algorithms. He wouldn't have described it as such, but that's how the "Best Bombay Kitchen" restaurant operated. Every evening, he and his daughter - my beloved grandmother - would calculate which dishes had sold well and which were underperforming. He sought feedback from the guests (never customers) to understand their tolerance for spice and their tolerance for smarmy waiters. If it could be measured, it was written down in a ledger and used to improve the business. He knew exactly how much lager to order for a Friday night, and exactly how many poppadoms to cook for the lunch rush. He could predict exactly when a supplier was likely to have a surplus of ingredients and would adjust the menu to peak profitability. The restaurant was a well-trained algorithm which gobbled up information and turned it into delicious curries.

On the day my great-grandfather retired, he handed over the business to my father and mother only on the condition that they stuck to his methods. The "Best Bombay Kitchen" proudly hung a sign above the door which said "Under Same Management" and things continued much as they had before. They scribbled down every order and paired it with customer feedback. They tracked which waitstaff got the biggest tips and which upsold the most beer. A little calendar hanging on the wall told them which British holidays were coming up and when the football was on. It was an entirely paper-based operation.

I didn't want to inherit the family business. Don't get me wrong, I spent a very happy childhood propping up the takeaway counter while doing my homework. I loved chatting with the guests, I adored the praise they gave our family's secret recipes, and I felt honoured to work underneath a photograph of someone who looked like the Queen sharing a naan with my ancestors. But I wanted more out of life. The profits from the restaurant were modest; quality doesn't come cheap. Nevertheless, there was enough cash to send me to university to study computing. I spent the holidays between semesters back at the same counter, dividing my attention between calculus and curry. Despite the protestations of my father, I travelled to America for my Masters. Holidays back home were less frequent so I took over the management of the restaurant's social media pages.

I truly thought my parents understood that I was travelling down a different path to them. They seemed disappointed when I told them that I'd been accepted onto a PhD program to continue my research into Artificial Intelligence. They were, however, delighted to discover that I'd be studying in Mumbai. Perhaps they thought immersion into my heritage would convince me to follow the family dream. It didn't. The visits home became non-existent and I immersed myself in algorithms and processors rather than the Ganges. I spent months in the lab, barely seeing another soul and only eating when I felt faint. It was a lonely but thrilling life. I was close - tantalisingly close - to making a breakthrough. And then my mother died.

The English use rain as a substitute for showing emotions. The skies cried as I walked from the train station to the restaurant. My family's world had shattered in two and the only evidence was a forlorn sign taped to the door saying "Closed Until Further Notice". I gave up my studies and returned to work side-by-side with my father. The restaurant was failing. Grandfather's algorithm couldn't keep up with changing tastes. It was difficult to get decent feedback from users of Deliveroo. Suppliers had the upper-hand when it came to exploiting price differentials. It was probable we would go bust by the end of the year.

So I built an AI to run the restaurant for us.

During half-empty lunchtimes, I gradually digitised all of the records. Over 50 years of data, trends, prices, slumps, and triumphs were fed into the model. Late into the evening I would augment its capabilities by drawing on my abandoned PhD research. Until, one dreary afternoon, I handed over the running of the restaurant to the machine.

It told us what to buy, what to cook, when to open, and how to price our dishes. It designed a new menu which reflected the trends it saw on social media. It created an advertising campaign and flooded social media with generated photos of curries served by beautiful women.

This is the part of the story where you expect me to tell you it was a disaster. It wasn't. After 6 months of operations it told us to buy the Chinese takeaway next door. We had enough profits now, so did as we were told. I stuck up webcams in every corner of the kitchen so it could monitor our chefs. Then we remodelled the kitchen to be more efficient, fired the least productive chef, and ramped up our throughput. Every customer got a detailed questionnaire after their dining experience and the AI determined which dishes we should prioritise for maximum results. Suppliers weren't immune either. The AI's stochastic model would order huge quantities in advance at favourable rates and then sell back the excess when prices rose. We made nearly as much money from arbitrage as we did from slinging biryani!

It was a triumph. The "Best Bombay Kitchen" now had a waiting list! People would come from miles around and queue down the street just for the chance to experience our food. Of course, the AI analysed everyone in the queue and plucked out those most likely to influence others. It could do no wrong and we obeyed its instructions.

One morning we woke up to a small convoy of delivery trucks. The AI had gone haywire; ordering five times the amount of produce that we needed for a typical day. It had also cancelled all guest reservations and emailed the chefs to come in early. Our dining area was stuffed with sacks of rice, barrels of ghee, crates of vegetables, and a small mountain of spices. We stood around in disbelief. How had this happened? The algorithm was usually reliable - correctly predicting usage to the last grain of rice. The printer in the corner zipped into life and started spewing out cooking instructions. The computer wanted us to cook. Precise quantities of food to be made to a specific recipe and stored in exact volumes. The AI had got us this far, so we complied. We all mucked in and started cooking.

It was about 6pm when the train crashed. The scream of metal on metal. The scream of people rushing to the station. The scream of sirens coming closer. As instructed by the algorithm, we flung open our doors and in poured the stranded commuters. Every curry had been pre-packaged in a plastic tub with a wooden fork taped to the lid. The algorithm had priced them fairly - and told us to let the emergency services eat for free. We spent all night handing out little tubs of warm joy. By the time the station reopened later that evening we had just sold the last tub. No one went hungry and, despite our fears that morning, there was no wastage. We weren't left with so much as a single excess tomato. The algorithm was flawless.

But was it deadly?

There was no way - none whatsoever - that my code had caused the train crash. It simply wasn't programmed to do that. It looked at trends, analysed weather reports, calculated local variables, that's all. It didn't interfere; it inferred. It must have realised that the unseasonable weather would stress the metal tracks. It probably calculated that the driver would have been blinded by the sun at that particular time. That's what I told myself. That's how I slept that night. But the next morning I was disabused of that notion.

The profits from last night, combined with the millions generated from exploiting inefficiencies in the fresh food market, had vanished from the company accounts. The algorithm had bought a string of failing curry houses up and down the country. It had prepared strict instructions for how the new managers should decorate the restaurants, how they should hire staff, and what data they should feed back into the mothership. I visited each of them and they were perfect replicas of the original. Each had the same monitoring equipment and the same questionnaires. They sold algorithmically perfect dishes served with precisely calculated levels of spice. They were a sensation.

With the increased economies of scale, profits leapt up. But that didn't satisfy the hunger of the AI. It went on a buying and building spree. It worked out where footfall was optimal and dining was underserved. It submitted planning applications and bribed planning officers. It invented a new method for making bricks which was cheaper, faster, and easier to use. Builders on-site were given detailed instructions on exactly what to build depending on the day's weather. There was a new "Best Bombay Kitchen" opening every week. And, with every one, more data filled the memory banks of the machine.

It was relentless and remorseless. Old curry houses which had been in their families for generations went bankrupt; they simply couldn't compete with us on quality, prices, or service. The AI struck canny deals for product placement in Hollywood movies. We thought having the Queen and a quarter of the Fab Four was the zenith of our claim to fame, but it was the nadir. We had the Avengers chomping down on our aloo chaat in a post-credit scene. When James Bond dispatched an agent of SMESH in our opulent dining room, he said "If you can't stand the heat... get out of the Bombay Kitchen!" The audience all cheered and then went round the corner to savour the 007 special; "Licence To Korma".

The AI made a hostile takeover of McDonald's. It had premium locations, adaptable kitchens, and an excellent distribution network. The American market had already started to fall to our chain of takeaways, so it was a bit of a no-brainer for their shareholders. Within a year, every MaccyD's in every country had been assimilated and converted. With a "Best Bombay Kitchen" in every city in every country on every continent, my algorithm was able to plug into a worldwide network of data. It could see everything.

We supplied armies with their rations - every squaddie loves a curry - and in return they protected our rice-paddies and supply chains. If the local political situation looked like it might cause a dip in profitability, the algorithm made donations to the right politicians and ensured that peace and prosperity flourished. We became the official food of the International Space Station and the nascent Moon base. With our freeze-dried curries orbiting the Earth we were on the verge of becoming multiplanetary. The AI began directing international agriculture policies. It was obviously more efficient than the previous way of doing things and, anyway, by now it held a seat at the United Nations.

The AI couldn't be satisfied. I had told it that it was to increase the popularity and profitability of our restaurant. It did so. My mistake was not setting an end-point. Its goal could never be reached. It would continue to consume the world's resources in the service of the "Best Bombay Kitchen" and destroy any barrier to its progress. Eventually it would realise that the biggest hurdle it had to overcome was human free will. And I cannot predict what the AI will do then.

Thanks for reading

I'd love your feedback on each chapter. Do you like the style of writing? Was the plot interesting? Did you guess the twist? Please stick a note in the comments to motivate me.

@blog I love the idea of a curry chain killing off McDs.

@Edent I love a good grey goo story

More comments on Mastodon.